Why Your Project Isn’t Unique And How to Deliver It Better

Happy Tuesday, Transformation Friends. Another week, another opportunity to go Beyond the Status Quo.

Today, we continue our look at the central ideas from How Big Things Get Done by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner, focusing on two in particular: the myth of uniqueness and the power of modularity.

“This project is different. It can’t be compared to anything else.”

Whether it is migrating to the cloud, building a new hospital, launching a digital service, or rolling out a major infrastructure project, the phrase is familiar.

It is a comforting belief.

It allows us to rationalize why schedules slip, budgets balloon, and risks go unacknowledged. But as Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner remind us in How Big Things Get Done, this assumption is dangerous. Most projects are not as unique as their sponsors claim. And success, counterintuitively, often comes not from reinventing but from repeating, what they call " finding your Lego.”

Today, we'll explore these two concepts and what they mean for transformation in government.

Grab your morning coffee, and let’s get started.

So You Think Your Project Is Unique

When a new initiative begins, many times we hear (or believe) it has never been done before. A government department implementing a new benefits system? That’s different from a corporate HR system. A public transit extension? That’s not the same as the one across the country. A military IT modernization? Totally unlike civilian digital transformation.

Except it isn’t.

Every project may have unique features like its context, stakeholders, or policies, but the patterns of success and failure are remarkably consistent. Budgets are underestimated. Risks are downplayed. Benefits are exaggerated. Timelines are optimistic.

When we think our project is too special to compare, we shut the door on learning from thousands of others that have gone before.

This is where reference class forecasting comes in. Instead of assuming uniqueness, we should place our project within a class of similar projects and draw lessons from the data:

What were the average costs?

How long did it usually take?

What risks commonly materialized?

By anchoring in the reality of history rather than the optimism of ambition, we can build more realistic plans.

We've seen this played out time and time again. Many IT projects are often described as singularly complex. Yet the same challenges, like underestimating application dependencies, overpromising timelines, and struggling with partner engagement, emerge every time. Treating each as a unique blind decision-maker to avoid the predictable traps.

The lesson in How Big Things Get Done is pretty clear: stop insisting your project is unprecedented. Start looking for patterns that have played out elsewhere. That is how you build realistic expectations and avoid the trap of overconfidence.

What’s Your Lego?

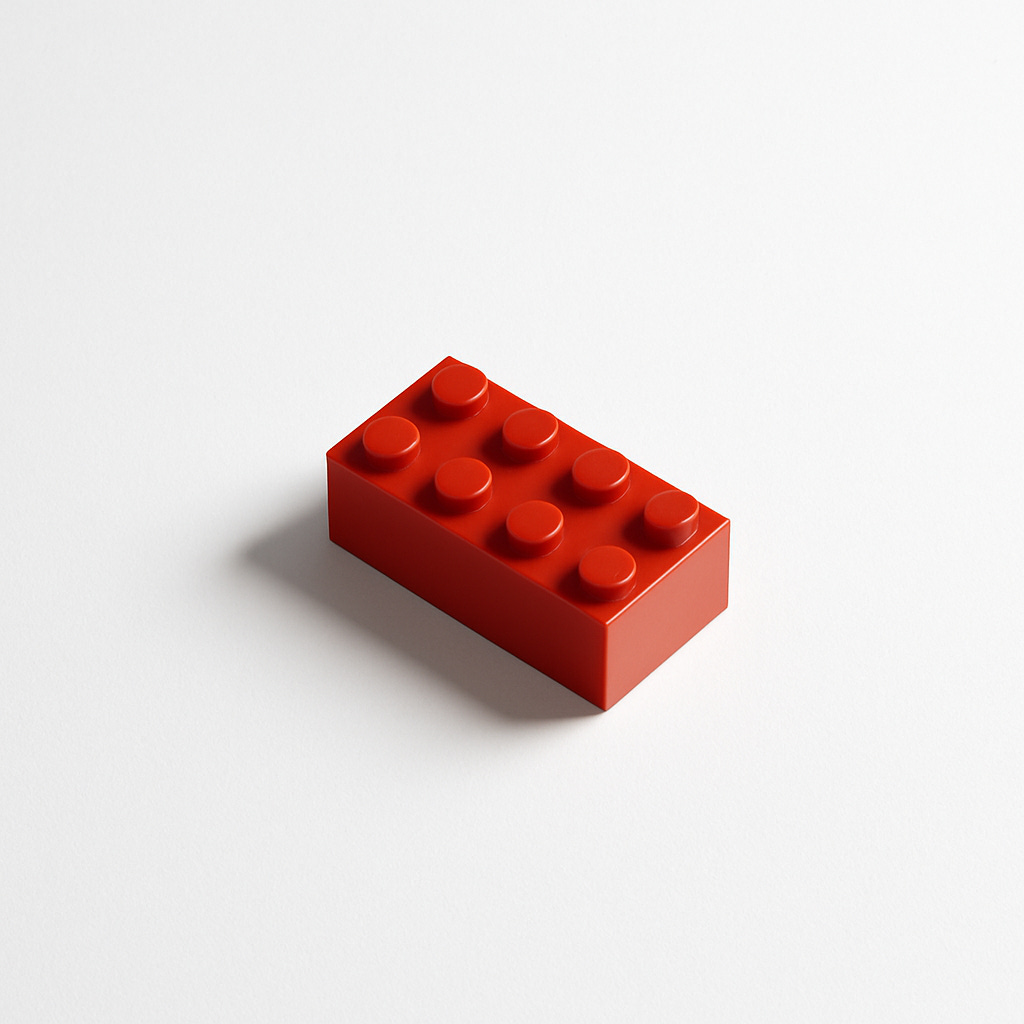

If rejecting uniqueness is about perspective, then finding your Lego is about smart design.

The metaphor is simple: big projects succeed when they are broken down into modular, repeatable units (like Lego bricks) that can be assembled predictably. The smaller and more standardized the block, the less risk and uncertainty in putting it together.

Take Apple stores, an example highlighted in How Big Things Get Done. The first few took time to design. But once the blueprint was perfected, the company replicated it worldwide. Each store was not designed from scratch. It was assembled from tested, reliable components. Offshore wind farms follow the same logic, reusing foundations, turbines, and processes across sites. Pixar, too, treats movies as modular: the characters and plots change, but the creative pipeline and production process are standardized.

The same principle applies in government. The UK’s Government Digital Service (GDS) created common service design standards so that new digital services didn’t reinvent the wheel. In Canada, the Government’s Digital Standards (while admittedly a lot less prescriptive and more principle-based) provide a flexible framework for modular, repeatable elements in digital service design. Even infrastructure projects are discovering modularity: hospitals built with prefabricated units, classrooms delivered through standard designs.

Here again, the lesson is clear: What is the repeatable unit in this project? Identify it, refine it for your context, and use it again. That discipline, reusing proven blocks rather than starting fresh, is what reduces risk, speeds delivery, and strengthens results. This is your Lego.

From Unique to Repeatable: How the Concepts Work Together

Those two concepts work nicely together:

Recognizing your project is not unique opens the door to learning from history. It helps teams draw on evidence, use data effectively, and better anticipate risks. The result is more realistic commitments and stronger delivery.

Finding your Lego encourages reuse and grounds you in repeatable practice. It is about seeing that successful delivery often comes from assembling proven blocks rather than creating everything new. That discipline builds confidence, reduces risk, and accelerates delivery.

Together, they shape how we approach transformation. Rather than overemphasizing novelty, they encourage anchoring in evidence. Rather than starting from scratch, they point us toward standardization and scale. When predictable patterns are recognized and modular solutions are applied, we can concentrate our energy on the parts of the project that genuinely demand adaptation and creativity.

But let's be clear: This is not about ignoring context. Every project will need tailoring. But the baseline is not a blank sheet of paper. It is a set of lessons learned and blocks already built. That mindset shift is what separates fragile ambition from durable delivery—start from there and build outward.

Applications for the Public Sector

Let’s explore some areas where these ideas can transform how we deliver our initiatives.

1. Digital Service Delivery

Too often, new services are designed from scratch. Departments argue that their program is unique, so existing design standards do not apply. The result: inconsistent experiences for citizens, higher costs, and avoidable risks.

The non-unique approach: recognize that most digital services share common features. Apply lessons from previous projects and use data from existing platforms to set realistic timelines, costs, and risks.

The Lego approach: adopt and adapt service design standards. Treat things like authentication, payments, and notifications as blocks. Build once, reuse many times. Citizens benefit from consistency, and government benefits from efficiency.

2. Policy Implementation

Many policy rollouts fall into the uniqueness trap. Leaders argue their reform is unlike any before. But the challenges like stakeholder engagement, communication, and resourcing follow predictable patterns.

The non-unique approach: treat new reforms as part of a reference class. Look at what worked and what failed in past policy changes, and anticipate the same recurring risks and opportunities.

The Lego approach: identify the standard policy tools and engagement strategies that consistently work. Treat them as blocks, then adapt only where context requires.

3. Program Administration

Often, new programs are pitched as one-of-a-kind to give them that shiny new look. But they almost always share recurring administrative needs. Things like application intake, eligibility checks, payment systems, and reporting.

The non-unique approach: acknowledge these commonalities and ground planning in the lessons of earlier program launches.

The Lego approach: treat program administration components like intake forms, eligibility engines, and reporting dashboards as reusable blocks that can be applied across multiple programs.

Leadership Lessons

These concepts carry important lessons as they remind us to let go of the myth of uniqueness, to embrace the evidence of history, and to lean on repeatable building blocks that make delivery more reliable.

1. Check Your Ego at the Door

The belief that “our project is different” often reflects pride more than fact. Humility is a leadership strength. Recognize that others have faced similar challenges, and their lessons apply to you.

2. Anchor in Evidence

Reference class forecasting is more than a technique; it is a mindset. Insist on comparing your project to a class of similar efforts. Use data to ground your expectations. Optimism may inspire, but realism delivers.

3. Find and Build Your Lego

Ask early: What is the modular, repeatable unit in this project? Invest in designing it well. Once built, use it again. Each repetition increases confidence and reduces risk.

4. Balance Standardization with Context

Not everything can or should be standardized. Leadership lies in knowing where to reuse blocks and where to adapt. The art is in balancing efficiency with flexibility.

5. Focus on Value, Not Novelty

Too many projects chase uniqueness for its own sake. The public does not care if a service is novel. They care if it works, if it is reliable, and if it delivers value.

Wrap up

Many projects are often framed as special, unprecedented undertakings. This mindset is costly. It fuels overconfidence, blinds us to evidence, and leads to reinvention. The truth is that while every project has unique aspects, the patterns of success and failure are consistent.

Those who succeed are those who embrace comparability and repeatability. They reject the uniqueness trap, learn from the reference class, and find their Lego. They understand that transformation is less about novelty and more about disciplined execution.

Here are three questions to reflect on:

Where have I assumed my project was unique, and how did that shape my decisions?

What repeatable building blocks could I identify and reuse in my current work?

How can I balance adapting to context with applying lessons from past projects?

The next time you hear someone insist their project is unique, ask them: What’s your Lego?

Until next time, stay curious and I’ll see you Beyond the Status Quo.