Think Right to Left: Defining the Why for Better Public Sector Results

Happy Tuesday, Transformation Friends. Another week, another opportunity to go Beyond the Status Quo.

Last time, we explored think slow, act fast and how deliberate preparation followed by disciplined execution improves results (Flyvbjerg and Gardner, 2023; Kahneman, 2011).

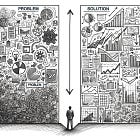

This week, we return to another central theme from How Big Things Get Done: think right to left, or begin with why. In Flyvbjerg and Gardner’s terms, this means deciding on the end outcomes that matter most for citizens and then reasoning backwards to identify the outputs, activities, resources, and milestones that will make them real. The authors stress that large, successful projects are rarely the result of diving straight into delivery. Instead, they begin with clarity about the destination.

Simon Sinek’s (2009) work Start With Why reinforces this point: leaders who clearly articulate the underlying purpose of their work inspire stronger commitment and alignment. For Sinek, starting with why builds trust and fosters intrinsic motivation, making it easier for teams to persist through challenges and adapt when circumstances change.

Grab your morning coffee, and let’s get started.

Why Starting with Why Works

Flyvbjerg and Gardner note that projects often derail when teams rush to solutions before clearly defining the desired impact. Activity takes centre stage, outputs multiply, yet outcomes stay vague or contested. The public sector is particularly susceptible to this, given the nature of political cycles and the pressure for visible progress.

Right‑to‑left thinking corrects this by:

Anchoring decisions in public value: Outcomes, not tasks or outputs, guide choices. This aligns with Rumelt’s (2011) argument that good strategy identifies a clear challenge, sets guiding policies, and defines coherent actions. Sinek (2009) adds that this clarity of purpose is what rallies people behind a common cause, enabling consistent decision-making even under pressure. He argues that when leaders communicate a clear "why," it taps into the limbic part of the brain responsible for decision-making and behaviour, making the purpose resonate on both an emotional and rational level.

Guarding against premature action: Kahneman’s (2011) work demonstrates that humans tend to lean toward quick, intuitive actions. A deliberate focus on outcomes forces a System 2 pause to check assumptions. Sinek reinforces this by suggesting that when the "why" is front and centre, it slows the impulse to act for the sake of activity and instead encourages actions that stay true to the underlying purpose.

Clarifying trade‑offs: When objectives conflict, leaders can compare options by their contribution to the end goals, echoing Robinson’s (1990) concept of backcasting to resolve competing pathways. Sinek’s framing supports this, noting that a clearly articulated "why" serves as a filter for choices, making trade‑offs more transparent and aligned with the ultimate mission.

Holmberg and Robèrt (2000) expand this by demonstrating that beginning with a clearly defined sustainable end state provides a stable reference point for decision‑making. In practice, this means identifying the environmental, social, and economic conditions that must be met for the project to be considered sustainable, and then working backwards to determine the policies, technologies, and processes needed. This approach helps teams avoid committing too early to solutions that may later prove incompatible with long‑term goals, ensuring that every step taken aligns with the overarching vision for sustainability.

Example: the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

In How Big Things Get Done, Flyvbjerg and Gardner highlight the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao as a case where right‑to‑left thinking shaped both design and execution. The aim was never simply to construct a museum. When architect Frank Gehry probed the underlying why, he discovered that the city’s leaders wanted more than an art space; they wanted a landmark capable of putting Bilbao on the global stage and sparking a cultural and economic renaissance. This meant first defining specific desired outcomes (increased tourism, job creation, and international recognition) before moving to design choices, material selection, or delivery methods. By anchoring decisions in these end goals, Gehry ensured that the building’s striking design served the city’s broader ambitions.

Example: Building a Bridge

Consider a simpler example: building a bridge. In many cases, the bridge is not the ultimate objective; the goal is to improve the movement of people and goods and potentially stimulate economic growth.

However, when the underlying "why" is examined, a bridge may not be the best solution. Improvements to ferry service, public transportation, or logistics infrastructure may deliver the same or better outcomes at a lower cost and with less environmental impact.

Defining the intended benefits at the outset allows planners to work backwards to identify the most effective option. If a bridge is chosen, this clarity helps set the right specifications, construction methods, and sequencing. The focus shifts from delivering a predetermined structure to achieving measurable outcomes that serve the public interest.

The Four Right‑to‑Left Questions

Flyvbjerg and Gardner’s framing can be broken into four sequential questions, which act as a structured decision-making pathway from purpose to execution:

Why: What measurable outcomes for citizens and the state are we pursuing?

What: What products, services, or policy changes are essential to reach those outcomes?

How: What activities, delivery models, and capabilities will create and sustain the "what"?

Who/When/How Much: Who owns each part, by when will it be done, and at what cost and risk?

The authors emphasize answering these in order, revisiting them regularly, and ensuring they shape business cases, plans, and governance decisions.

Applying Right‑to‑Left Thinking

Drawing on the principles in How Big Things Get Done and reinforcing them with insights from wider literature and practice, a practical step-by-step process could be structured as follows:

Write the Outcome Statement: Define a goal that is citizen-centred, measurable, and time-bound, making it clear enough that anyone outside the project team can understand what success looks like.

Backcast from the Target Date: Starting from the end goal, identify the essential preconditions and milestones in reverse order to ensure each step logically leads to the next.

Define Benefits and Measures: Choose only indicators that clearly reflect public value, assign accountable owners, and identify reliable data sources to track them.

Translate Outcomes to Outputs: Determine which tangible deliverables will directly influence the agreed‑upon indicators, avoiding unnecessary work that does not move the needle.

Choose Options and Minimum Viable Scope: Compare different approaches based on outcome-impact per unit of cost and risk, and opt for the smallest scope that achieves the desired results.

Build a Theory of Change: Explicitly map how activities will lead to outcomes and test the riskiest assumptions early to reduce the chance of costly missteps.

Design Governance Around Outcomes: Structure oversight so that funding and approvals are tied directly to evidence showing movement toward the desired outcomes.

Communicate the Why: Share the purpose in outcome‑first narratives, ensuring that internal and public updates reinforce the link between actions and the original purpose.

Connect to Think Slow, Act Fast: Right‑to‑left defines the destination; think slow designs the route; act fast executes, creating a clear and coherent chain from intent to impact.

I’ve written about specific tools and techniques that I’ve used to achieve this before. You might want to have a look at these previous posts:

Pitfalls to Avoid

Flyvbjerg and Gardner caution against the following common traps that can derail right‑to‑left thinking in practice:

Vague or conflicting outcomes: When end goals are unclear or contradictory, teams struggle to prioritize actions, resulting in wasted effort and a diluted impact. Clear, agreed‑upon outcomes keep all stakeholders aligned.

Proxy metrics that drive the wrong behaviours: Relying on indirect indicators can encourage activity that appears to be progress but fails to deliver public value. For example, counting kilometres of road built without measuring travel time reductions may reward quantity over actual benefit.

Over-engineering the scope beyond what affects outcomes: Adding features, specifications, or deliverables that do not improve the agreed-upon results wastes resources and increases risk. Keeping the scope to the minimum needed to achieve outcomes improves focus and efficiency.

Treating the plan as fixed rather than updating as evidence changes: Rigidly following an initial plan can lock teams into ineffective paths. Regularly reviewing and adjusting plans based on new data ensures delivery remains on track toward the intended outcomes.

Sinek would add that a poorly communicated or weakly defined "why" can undermine even the best technical plan, as stakeholders disengage without a clear reason to care.

Leader’s Checklist: Making Right-to-Left Thinking Work in Government

Set the Why

Draft outcome statements in clear, citizen-friendly language, including target dates and measurable results.

Select 3–5 outcome indicators with named accountable owners.

Work Backwards

Use backcasting to identify milestones and dependencies from the end goal to the present.

Map key assumptions and design tests to address the riskiest early.

Design for Value

Compare delivery options based on their impact on outcomes (economy, efficiency, effectiveness, and equity) per dollar spent.

Choose the minimum viable scope that delivers outcomes; expand only with supporting evidence.

Govern What Matters

Make approvals contingent on evidence of movement toward outcomes.

Require change requests to show a clear and quantified impact on agreed-upon outcomes.

Communicate the Why

Centre all updates around outcome-first narratives that connect actions to purpose.

Explicitly link individual roles, team responsibilities, and funding to outcome accountability.

Wrap up

Flyvbjerg and Gardner’s think right-to-left approach offers a disciplined way to keep strategy anchored in public value: define the why, work backwards, and let evidence steer delivery. Combined with think slow, act fast, it creates a resilient link from intent to impact.

Here are some self‑reflection questions to help you consider how well you are applying right‑to‑left thinking in your own context

Do my current initiatives have outcome statements that a citizen, like my neighbour, would understand?

Do dashboards lead with outcomes, not activity counts?

At the next gate, what evidence will show that we are moving indicators in the right direction?

Until next time, stay curious and I’ll see you Beyond the Status Quo.

References

Flyvbjerg, B. and Gardner, D. (2023) How Big Things Get Done. London: Penguin Press.

Holmberg, J. and Robèrt, K.-H. (2000) ‘Backcasting from non-overlapping sustainability principles’, International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, 7(4), pp. 291–308. doi:10.1080/13504500009470049.

Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. Toronto: Doubleday Canada.

Robinson, J. (1990) ‘Futures under glass: a recipe for people who hate to predict’, Futures, 22(8), pp. 820–842. doi:10.1016/0016-3287(90)90018-D.

Rumelt, R. (2011) Good Strategy/Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters. New York: Crown Business.

Sinek, S. (2009) Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. New York: Portfolio.

Really like this framing! We just finished another one of our Digital Executive Leadership Program cohorts and "Getting Big Things Done" is one of the books we provide people as follow-up reading. The intersection with how you've framed it here, and concepts around design thinking and agile approaches are really interesting. Such a bias to be "solution focused" in the public sector, which sounds good at first glance, but leads to all the bad outcomes we see when we don't spend time upfront thinking about what the actual problem is we are trying to solve. Thanks as always for sharing your perspective!

The public sector will always have trouble delivering results. Parkinson's Law holds at all times:

1) The work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.

2) The number of workers within public administration tends to grow regardless of the amount of work to be done. This is attributable mainly to two factors: public servants want subordinates, not rivals, and public servants make work for each other.

In Canada, we see both parts of this law in full force. The civil service has grown incredibly over the last ten years. What's even more germane is that it takes the government to tell the civil service to find efficiencies. If efficiencies were always there to be found, why did it take the government to tell management to find them? Shouldn't management have already discovered all efficiency gains? Why wasn't the civil service already on the production frontier? In some sense, why does the government need to suddenly tell management to do its job? The answer is easy: Parkinson's Law.

What Parkinson's Law really shows us is a window into public choice theory. The civil service is tightly connected to the rent seeking sector of the economy and that drives all kinds funny distortions. The goals of government projects are rarely what it says on the tin, often ending up as redistribution enterprises to favoured industries or special interest groups. Market forces for votes work just as powerfully in politics as they do in the rest of the world - except power is the goal, not profit. And if a government project completely fails, bureaucratic process is there to rescue everyone from accountability - defeat is an orphan. The Phoneix pay system is case in point.

There is a reason we don't want the government to run a command economy. We implicitly recognize, or at least we used to, that the centralization of power leads to disaster. It's unfortunate that we need government to solve some externalities (and it would be great if we could hold government to only that goal!), but if we can find a way around it, we would get twice the output at half the cost.

Parkinson's Law is an absolute force of human nature.